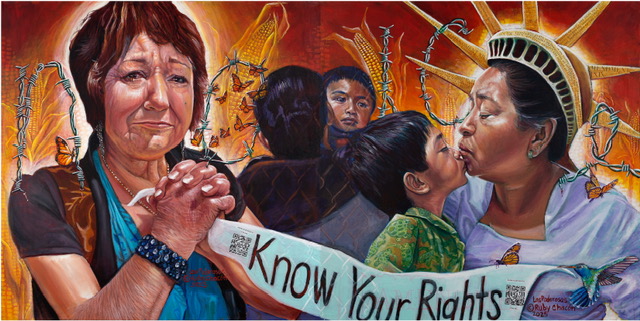

Artists Ruby Chacon and Isabel Martinez describe their work. Note that this mural is a work in progress.

Ruby Chacón (she/her/ella) – Know Your Rights.

Ruby’s recent work on immigrant rights represents survival through culture, resistance of the oppressor, and the ever-present ancestral knowledge that spiritually guides us and allows us to understand our place within a larger ancestral lineage, fostering a deeper connection to our roots and heritage. The painting’s theme of survival through culture is deeply resonant. It asserts that ancestral knowledge isn’t passive; it’s active, guiding, and defiant.

By juxtaposing nurturing maternal imagery with the violence of current immigration policies, Ruby forces viewers to confront the contradiction: how systems attempt to erase what is sacred and life-giving. The imagery profoundly illustrates the oppression of our identities as Chicanas/Latinas/Indigenas.

The “Know Your Rights” painting features two main womxn figures. They are both mothers who have recently passed away, making them our new ancestors, our spiritual protectors.

The woman on the left side is Virginia Chacon, the mother of the artist. Ruby stated, “ I chose my mom as one of the main figures because I know that had she lived a few months longer, she would have put her own elderly body in the line of fire to protect anyone from being hurt. My mom never thought about what would happen to her; she only wanted to correct an injustice. I live to continue her legacy of justice through the care and support of others that she exemplified.” Ruby’s quote about her mother is a testament to intergenerational activism rooted in love and sacrifice.

The other main figure is Ana Ruth Uribe, mother to the artist’s dear friend, educator, and social justice activist Ana Quiñonez. Ana Ruth’s depiction, kissing her grandson beneath a crown embedded with the 14th Amendment, reclaims the Statue of Liberty’s promise, not as a distant ideal, but as a lived, intimate truth. It’s a visual assertion that constitutional rights belong to all, especially those who have been historically excluded. The crown is a brilliant act of visual storytelling. It’s not just symbolism, it’s a reclamation. It says: “These rights are ours. Our ancestors wear them.”

Virginia Chacón and Ana Ruth Uribe are not just maternal figures; they are elevated to ancestral guardians. Their presence in the painting transforms grief into guidance, loss into legacy. They are not idealized; they are real, recent, and personal. They cannot be dismissed as abstract or distant. Both mothers represent pure love and our resistance to oppressive policies.

The butterflies represent migration, strength, and resilience. They are the monarch butterflies that migrate from Michoacan, Mexico, to Canada and back. For the butterflies, there are no borders. Much like many in our community, they survive these migrations despite the numerous obstacles and borders they must overcome.

The hummingbird holds up the “Know Your Rights” banner, exemplifying the contradiction between the joy it brings and the feistiness it exudes when needed. They are small and beautiful, but if you try to attack them, they are fighters. Do not underestimate the hummingbird; despite their beauty, they are fierce!

The corn is integrated into the background and spiritual lighting around the two mothers. The corn is a reminder of the nourishment we obtain from our culture. We sustain ourselves when we feed our souls with the nutrients rooted in our land.

The mother walking away with her child in her arms symbolizes the countless families affected by ongoing deportations. A faint, almost invisible fence stretches across their path—an ominous presence that suggests looming danger without fully enclosing them. More striking is the barbed wire, twisted into the words “No ICE.” Despite the pain, these womxn press forward, driven by love and resilience. They refuse to be broken by the violence inflicted upon them. Instead, they embody fierce protection and radiate love, even as they bear the wounds of systemic cruelty.

Isabel Martinez (she/her/ella) – We The People

“We the People” (working title) is a diptych on canvas depicting Isabel’s maternal and paternal grandmothers, each represented as symbolic pillars of resilience and cultural continuity. The work reclaims foundational American imagery —the Statue of Liberty and the U.S. Constitution —through the lens of immigrant and Indigenous matriarchal strength.

Isabel’s maternal grandmother (left) is represented as the Statue of Liberty. She holds the torch to light “the way to freedom and down the path of liberty.” As a widowed mother of 16 who migrated to the U.S. in the 1970s, she embodies the strength of women who hold families together through migration and hardship. She reclaims Lady Liberty, not as a distant icon, but as a lived reality of immigrant women who embody freedom through endurance and love.

Her paternal grandmother (right) is depicted sewing on her Singer machine with fabric that reads “We The People” from the U.S. Constitution. As a master embroidery artist, she sews on a fabric that is embroidered with images of Indigenous food: maize, calabazas, and frijoles. Also known as the Tres Hermanas (Three Sisters), Indigenous peoples have cultivated these companion crops for millennia in Central and North America. The inclusion of tres hermanas affirms that Indigenous practices are not of the past; they are of the present, nourishing, and sacred. Her grandmother’s art elevates embroidery as a legitimate art form and a vessel of cultural memory. She literally weaves Indigenous knowledge into the fabric of American identity.

The original peoples of this land are still here. Their traditions, foods, and art forms are foundational, not forgotten relics, but living legacies. The depictions of her grandmothers embody the sacrifices made by women who are forced to leave their home countries in search of a brighter future. Both grandmothers are portrayed as creators, protectors, and cultural transmitters. Their work and artistry, whether through migration or embroidery, is revolutionary. By integrating “We the People” and the Statue of Liberty, her work critiques exclusionary narratives and redefines who belongs in the country.